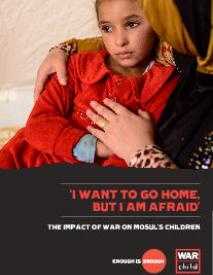

'I want to go home, but i am afraid' : The impact of war on Mosul's children

In early July 2017, the coalition1 military offensive to oust so-called Islamic State in Iraq and Syria (ISIS) from Mosul reached its grisly climax. Civilians have borne the brunt of this conflict, with half a million school-aged children amongst the displaced. 2 Amid the horror of the ISIS occupation of Iraq’s cities and villages, it is comforting to believe that once the group has been defeated militarily, normality will return and traumas inflicted will quickly recede. Yet in the medium to long-term, the suffering of Mosul’s children looks set to continue. This report seeks to highlight the immediate and ongoing needs of children affected by the conflict in Mosul and Ninewa Governorate.

Hundreds of thousands of children have spent up to three years trapped under ISIS control and endured deeply traumatising experiences. Children have been forced to witness executions and the murder of their friends and family. Their education has been disrupted and replaced with exposure to a warped and violent ideology. It is hard to truly appreciate the harm these experiences will have had on these children – but what is clear is the need for dedicated and prolonged support for the harm to be addressed.

Though the fighting has wound down, counter-insurgency to root out ISIS members who fled Mosul continues. We have learnt of boys accused of ISIS membership being detained and ostracised from their communities, and of families being collectively punished for having a family member in ISIS.3 It is clear that the impact of injustices committed against these children will continue to ripple out across their lives, leaving them vulnerable to further discrimination, marginalisation and trauma. Furthermore, these crimes, and the brutalisation children have experienced, could contribute to a cycle of violence that will create a new generation of marginalised young adults vulnerable to the appeal of extremist ideologies.

Humanitarian organisations, including War Child UK, have been delivering services to children close to the front line of the fighting. Many agencies report that with the liberation of cities such as Ramadi and Fallujah, humanitarian funding has quickly dried up as donors shift their focus to the next hotspot in the conflict. The UN humanitarian appeal for Iraq is currently 45% funded, with education having received only 33% funding.4 The offensive against ISIS and associated humanitarian response will last at least until the end of the year. The funding previously pledged must be disbursed as soon as possible. Donors must also make further multi-year commitments to bridge existing and future gaps in funding for humanitarian response and stabilisation efforts. This will give humanitarian actors the opportunity to adapt their response plans so as to meet the needs of the most vulnerable.5

Children have a long road of recovery ahead on which they will need to be protected from harm, feel secure and be supported to access a quality education. Prioritising the mental health and well-being of children and adolescents is a key step that humanitarian agencies, donors and national authorities must take if they hope to achieve the vision of long-term peace and stability in Iraq.

Geachte bezoeker,

De informatie die u nu opvraagt, kan door psychotraumanet niet aan u worden getoond. Dit kan verschillende redenen hebben,

waarvan (bescherming van het) auteursrecht de meeste voorkomende is. Wanneer het mogelijk is om u door te verwijzen naar de bron

van deze informatie, dan ziet u hier onder een link naar die plek.

Als er geen link staat, kunt u contact opnemen met de bibliotheek,

die u verder op weg kan helpen.

Met vriendelijke groet,

Het psychotraumanet-team.